Bad Ass Peacock Bass of the Amazon with River Plate Outfitters

By Bill Blanton

In the world of freshwater fish, the peacock is the badass. He’s the snotty kid with the mean attitude. He’s the playground bully who’ll take your lunch money, bloody your nose; send you crying to the teacher after recess.

He’ll straighten your hook, pop your leader, and wind your fly line through a maze of roots and underwater tree branches. Give him a chance; he’ll break your rod.

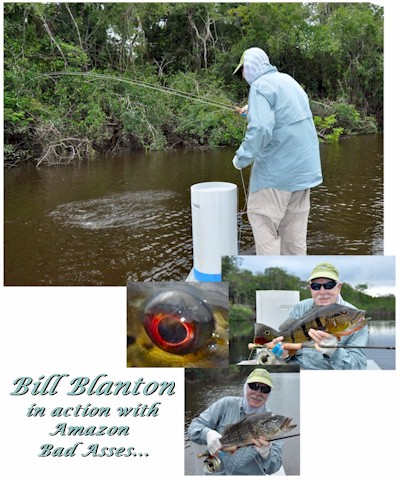

Once you subdue him and get him in the boat, he glares defiantly with those blood-red eyes as if to say, “So … is that the best you’ve got?”

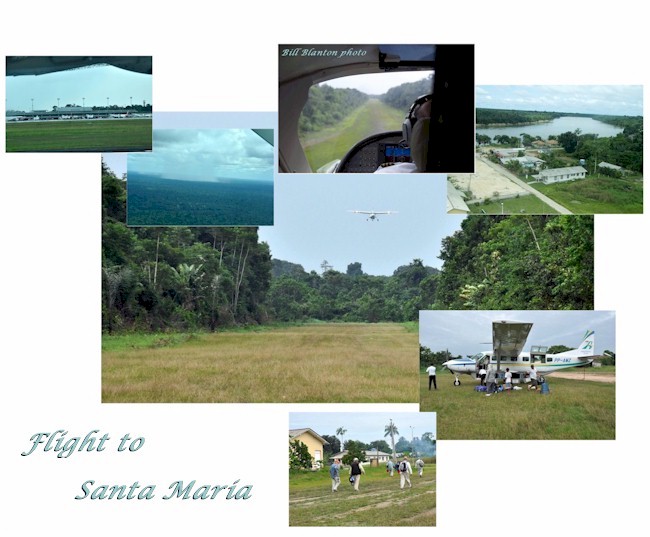

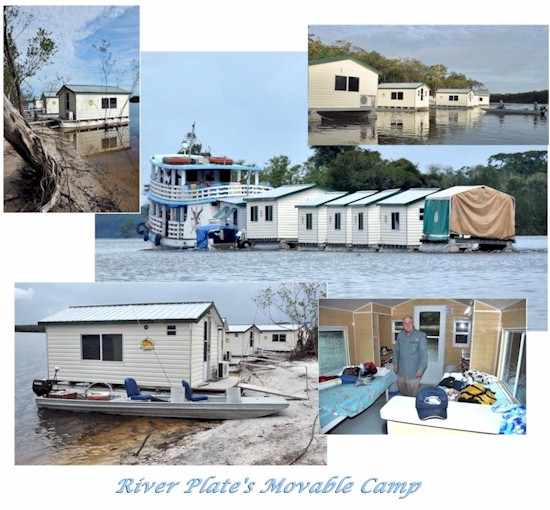

In mid-January, I joined Dan Blanton and five other pilgrims for a journey into peacock country. From Miami we flew to Manaus, Brazil, where two massive river systems, the Rio Negro and the Rio Madeira, join the Amazon. We spent one night there in a luxury hotel, and then flew by single-engine, 12-passenger prop plane to the tiny community of Santa Maria on the banks of the Rio Branco, a tributary of the Rio Negro. We boarded a launch at Santa Maria, motored downstream on the Branco to its junction with the smaller Rio Xeriuni, then headed back upstream a ways on the smaller river until we encountered our mobile camp — four air-conditioned cabins for anglers, a cook shack, dining hall, guide quarters and generator barge — all mounted on pontoons so they could be towed from site to site by a riverboat “tug.” The camp moved three times during our eight days on the water.

By mid-afternoon of the first day, Dan and I were rigged and on the water fishing out of a 21-foot jon boat, equipped with 30-horsepower Suzuki and stern-mounted trolling motor. Our captain was Moe, the head guide. For about an hour or so, Dan and I politely took turns manning the bow, with one angler resting while the other fished. It only took a few hard pulls from peacocks to change that arrangement. For the rest of the six-and-a-half fishing days, we both cast at the same time, one from the bow, the other from midships. We alternated positions daily. We fished it like it was a job, casting continuously, pausing only to change flies, grab a drink of water or stretch weary muscles.

The work paid off in fish. Over the six-and-a-half days, we caught 270 fish ranging from two to 14 pounds. There were several other double-digit beauties and a whole bunch of seven- and eight-pounders that put a good bend in our rods. We caught all four species of peacock common to our area: the Azul, the Butterfly, the Paca and a fourth whose name I could never master, a fish that looked like a blend of Butterfly and Paca. In total, our group of six anglers caught 909 fish over the same period. One angler, John Waldum, landed fish of 22 and 18 pounds. We also caught a mixed bag of piranha, oscars, dogfish and other weird species endemic to the Amazon region.

The fishing was brutal. We were casting stout nine-weights equipped with Rio Tropical Outbound Short intermediate lines, frequently out to 70, 80, 90 feet, with large, wind-resistant flies. On no other fishing trip have I cast so many times at such distance. Each morning, I’d strip line off my reel until there were only a few turns left around the arbor, load it into the absolutely essential vertical line management device, in this case a travel bucket from Sea Level Fly Fishing, and go to work. For efficiency, we made a lot of casts with water hauls instead of aerializing the line. But there were times when, for accuracy’s sake, we had to false cast a few times before placing the fly.

With the two of us casting at the same time, large hooks were continually flying through the air around and over the boat. I only hit Dan three times, thankfully, in the back with the hook eye instead of in the face with the point. He was kind enough not to return the favor.

Accuracy was essential. The dynamic of the Amazon riverbank is that large trees, up to 50 or 60 feet in height, grow right up to the water’s edge. In times of high water, the bank erodes away from the root systems, and the trees fall in the water. On a typical shoreline, you don’t encounter one or two logs. Instead, it’s a maze of very large fallen trees, rotting logs, entangled branches — peacock heaven but hell for anglers trying to place a fly in an unobstructed spot.

The trick was to drop the fly as close to the obstructions as possible, swim it though the tangle of branches, then let it sink a bit once it reached the open water. Oftentimes, the water by the banks would be three to six feet deep. That changed, of course, depending on overall water levels. During our trip, water was high, but not unfishable.

A common exchange after one of us seemed to get a bump on the retrieve would go like this:

“Bite?”

“Wood.”

“Damn.”

As a guide in South Florida, I’m used to poling my boat over to a mangrove shoreline to help an angler pluck his fly out of the branches. I never make a big deal out of it. It’s all part of the game, so I didn’t feel bad at all when our Brazilian guides had to troll or paddle to a branch so I could dislodge my fly. Call it karma.

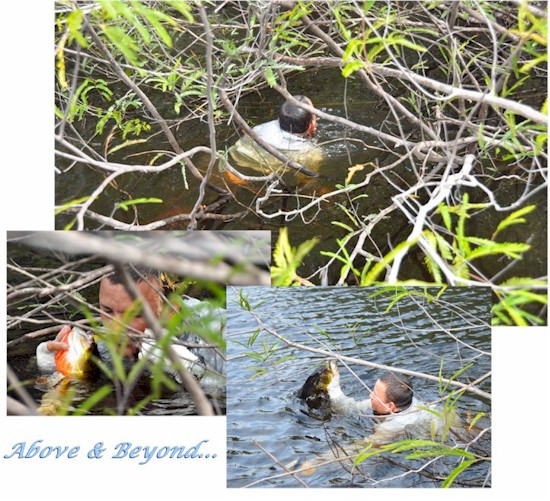

However, it was above and beyond the call of duty when two guides had to dive into the water to retrieve fish that had tangled themselves up in the roots.

Before Brazil, I’d heard talk about how hard-pulling peacock bass are. Since fishermen are known to exaggerate, I was somewhat skeptical. Anglers said they used “gorilla” leaders of straight 40-, 50- or even 60-pound mono. I was determined not to do that since it sounded like a good way to break a rod or lose a fly line. Instead, I employed one of Capt. John Quigley’s excellent five-foot twisted leaders for a butt section, and then attached a three-foot segment of 40-pound mono for a tippet. The twisted leader is created from 20-pound mono, but its built-in stretch gives it a cushioning factor that reduces break-offs and still protects line and rod.

The pull? That was no bull. The first take, even from a small fish, is a shock. You’re stripping in the line on the retrieve, when, suddenly, it stops. I don’t mean you get a jolt; I mean the line stops.

Then it goes the other way … fast.

I’ve pulled a lot of snook out of the mangroves over the past 18 years. When a snook turns and heads for the roots, I try to steer him the way he wants to go and use his own momentum to keep him out of the bushes.

You can’t do that with peacock. You’ve got to pull straight back against the run — immediately — and not give an inch. Then you’ve got to keep pulling for all you’re worth, being careful to play the fish off the butt of the rod instead of the more fragile tip, all the while hoping your guide can get the trolling motor turned around quickly enough to ease you away from the bank.

Forget the reel. Both Dan and I lost large fish trying to put them on the reel. (On the other hand, John Waldum lost his line and 100 yards of backing to a fish he hooked in the open water and had to play off the reel).

The fight continues when you get the fish away from the woods. The peacock will jump, make short runs and dive under the boat. Once it’s subdued and in hand, the game’s still not over. More than once during picture taking, a seemingly dormant peacock suddenly came back to life while being held for the camera, wrestling itself out of our hands and thrashing around in the boat. This might happen three or four times with one fish. Even after several minutes of posing for photos, they were very strong during the release. Red eyes glaring, they’d give one powerful tail kick and be gone.

More about that pull: On the second day, when we’d gained a little experience, I got a hit from a very large fish, perhaps the largest we encountered during the entire trip. I was an instant late in controlling the line, so the fish accelerated toward the bushes. When I finally got a good grasp on the line, it was too late. He had gained too much momentum. I pulled. He pulled. The leader broke.

The 20-pound twisted leader butt section held, but the 40-pound tippet parted at the knot to the fly. I’m real careful with my knots and proud of how they hold up, but after studying the tippet for a few minutes, I abandoned the Improved Homer Rode Loop Knot I’ve used for tarpon, sails and other large critters and switched over to the knot Dan was using, the Harro version of the Non-Slip Loop Knot. No more problems after that.

We all exhibited combat wounds. Under normal fishing conditions I wear sungloves on both hands. On the middle finger of my rod hand, I place a finger guard. After three days of battling peacocks, I had to increase the protection to three finger guards on the rod hand: one on index, one on middle and one on the third finger. Under the finger guard on the third finger, over the big open bleeding blister, I placed a band-aid and over-wrapped that with a one-inch wide strip I’d cut from a bandanna. I wound the rest of the bandanna around my palm to cushion it and slid the sunglove over the whole bandaged mess so my hand resembled a small pillow with fingers sticking out of it.

On the line hand, I placed finger guards on thumb and index finger. By Day Four, the back of my line hand swelled up in a puffy mound, a reaction, I guess, to the constant rapid stripping. My back hurt, my shoulder ached. The first few casts in the morning were reminiscent of a pitcher warming up in the bullpen: A few easy throws of 20 feet or so, a few more out to about 30 feet, then a little more velocity, a 40-footer with a little heat on it, then, finally, the fast ball, a long cast into the wooded banks.

Even landing 270 fish, we encountered dry spells. We’d work a bank for a while catching nothing, then one of us would get a bite. Sometimes, that’d be the only fish in the spot, but, more often, one fish meant others, perhaps many others, in the vicinity. The last day of fishing started slowly until we found a pod of Paca lying in the deep water off a sharp point. We cast our flies up to the point, stripped a couple of times and then let our flies drop for 10 to 12 seconds before we resumed the retrieve. The hit would come on the first or second strip after the drop. We caught seven or eight fish there before they wised up.

Later that day, we worked a U-shaped indentation in the main river channel right across from a small village. In a stretch of about 40 feet, we landed 23 fish in an hour and a half, the largest running seven pounds. That afternoon, we hit the same spot again and caught another 10 or so, including our best fish for the trip, Dan’s 14-pounder. Our total for the day was 52 fish, so three-fifths of our grabs came from one spot.

Based on my experience of just one trip, fly selection is important but not critical. The most important thing was to put the fly in the right place.

Still, some patterns worked better than others. We both caught fish on a wide variety of flies and fly types. My favorite was a version of Rob Anderson’s Reducer tied, like almost all of my flies for the trip, by Bill Logan of Roseburg, Oregon. It was buoyant enough to swim though the branches but heavy enough to sink effectively once it reached the open water. The orange, yellow and blue bucktail and orange grizzly hackle seemed an appealing color combination. The fish loved it. The Reducer was most effective in the morning. In midday, fish seemed to want a change-up. One day, I pulled out a 3/0 black and yellow Enrico Puglisi tarpon fly. The “Rotten Banana Peel” fly worked great for an hour or so, then lost its effectiveness. Another great midday fly was a small chartreuse and white Clouser. Late in the afternoon, fish seemed to want something with more bulk, so I changed to variations of Dan’s Flashtail Whistler. The most effective color combo for me was chartreuse and white.

Dan fished a wider variety of flies than I did but probably caught most of his larger fish on versions of the Whistler.

Because of the high water levels, topwater flies weren’t effective. Everyone tried them for a bit — Dan cast a Ron Dong Crease Fly for an hour or so on our last morning — but the fish just wouldn’t come up for it. Intermediate lines with bulky or weighted flies were the ticket.

The trip was organized by Keith Kaneko of Angling on the Fly. Unfortunately, Keith was not able to accompany us. River Plate Outfitters did a magnificent job of getting us there and putting us in a position to catch fish. Our camp host, John Silvia, was a genuine delight, a great organizer, host, fishing adviser, emergency field surgeon. Guides were professional and capable. Food and accommodations on the river were first-class.

It was a great trip for a great fish.

To Book a trip or learn more about the River Plate Operation Contact Keith Kaneko of Angling on the Fly Travel Service